THE CALL OF CHoRNOBYL

Note: “Chernobyl” is the Russian version of the word. In Ukraine, “Chornobyl” is the proper spelling.

I have wanted to visit Chornobyl since I was a young man. Over the years, I've read more books about Chornobyl, nuclear science, the history of the nuclear bomb, radiation, and Soviet history, than any other subject. While I don't consider myself an expert by any means, these subjects have fascinated me as long as I can remember. I've also been spoiled for choices on other ways to immerse myself in the exclusion zone - the cultural impact of Chornobyl cannot be overstated, as it has been reflected upon both literally and figuratively in books, media, video games, movies, and TV shows. Primarily, my interest was stoked by the acclaimed survival horror video game franchise S.T.A.L.K.E.R., a series in an expanded version of the Chornobyl Exclusion zone that I have spent many hundreds of hours exploring. Beyond that, the classic novel Roadside Picnic, and the Tarkovsky film Stalker, have opened other avenues to explore the mysteries of the zone.

Chornobyl represents the horrific consequences of great ability trapped in indelicate hands. Where our other failures take human lives and can locally devastate an environment, nuclear contamination does both of those and is functionally permanent. To put things in perspective, the earliest point in human history is generally believed to have been recorded 5,000 years ago. Pripyat, the city built to house the workers of Chornobyl and it's associated facilities, will not be conventionally inhabitable for twenty times the total length of recorded human history.

When we think of the most significant events in the new century, 9/11 certainly marks the beginning of a global change towards larger scale imperialism and the slow annihilation of civil liberties in the western world. Every facet of our current political climate is reflected in the world that came after the towers fell. In the preceding century, Chornobyl precipitated the downfall of one of the largest industrial empires in history. The disaster at Chornobyl revealed to the globe the grave faults in the Soviet system - and how, when in conflict, the ideological imperative must bend to scientific truth. The disaster was not just a local issue, but a radioactive catastrophe that spread a plague of contamination from Kiev to London. More startling still is that it could have been dramatically worse - If the Chornobyl divers, Bespalov, Baranov, and Anenenko, had not released the water valves beneath the blasted reactor, the molten core could have reached the water and triggered another explosion. A second disaster would have created an uninhabitable white zone from Portugal to Moscow, and would have triggered a mass extinction event across the globe. The consequences of this event are hard to exaggerate. Chornobyl is where humanity came to the very brink of extermination.

To me, our quest for nuclear power has been like that of Icarus, who abused his power and strove too far, and fell to earth to suffer for his hubris. Perhaps even more appropriate, the fission of the atom is like Pandora's box; a perilous, mercurial force belonging only to the gods, and having loosed it, we must suffer the consequences eternally. The godlike destruction of nuclear weapons, and the seething permanence of radioactive contamination, are to me the closest mankind has come to truly cosmic power, power wholly outside of our control.

Please note that some of the details on this might be wrong. I took contemporaneous notes on the journey, but the file was deleted. I might have some dates, numbers, and locations mixed up. If you have any questions or corrections, let me know.

I had invited many people on this trip, and of them, only my aunt Jan was able to join. She is a wise and insightful woman, so she made a great travel companion. In the early morning, we met with the group near the metro station and checked ourselves in with the guide. The drive to the first check point was about an hour. At some point on the flight into Kiev, I realized that, my god, I'm actually going to do it. I'm actually going to Chornobyl. That feeling was a rush. I felt it again as I watched the trees speed past the bus.

We filled out documentation at the first check point. I knew they would be selling souvenirs, but I hadn’t thought about what it would look like juxtaposed with the military checkpoint in the background. The sight was odd - I love souvenirs, and I’m into the grotesque, but I wonder how the people behind the stands feel about selling merchandise depicting the worst ecological disaster in their nations history as a fleeting figment of pop culture. It isn’t all bad, though: Some of the money goes to help the local economy, and other money goes to help the settlers - the old matriarchs who returned to their devastated villages after the evacuation.

On the way into the exclusion zone, the guide indicated that he is not, in fact, a guide, and that we are not tourists, because there was no legal tourism in the zone. Instead, he is a scientist, and we are his assistants. This is a legal distinction that becomes important later - it means we are placed under stricter surveillance and must obey extra rules and regulations, including a curfew. Having said that, he then outlined the laws that we would be breaking throughout the trip, clarifying that he would did not want to be in any photographs while breaking laws. Technically, we are not allowed in any buildings within the exclusion zone, but he doesn’t believe that would make for a good trip. In short, “It doesn’t make sense to go to Pripyat without going into the buildings. You don’t get to see how big the city is just by standing on the ground.”

A couple things surprised me on the way to the first location. I was aware of people called Stalkers, who intrude into the zone to steal materials to sell on the black market, but I didn’t know that it was a direct reference to the book Roadside Picnic, which describes a very similar activity with the same term. I had thought that Roadside Picnic was just popular among aficionados of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. video games, I hadn’t realized that its had such a cultural impact. This was clarified when we stopped at a canteen called ”Roadside Picnic.” Amusingly, the fare was almost exactly like that of the STALKER games - tea, vodka, bread, sausage, and canned meat.

I was also surprised at the sheer volume of industry that remains in the exclusion zone. I knew that there are a lot of tourists, but I had no idea that the town of Chornobyl has two thousand people who live and work in the zone. Those who remain are guards, police, and laborers and engineers, who build and maintain the new containment facilities, dismantle the old object shelter, run a wood processing plant, transport spent fuel rods to containment, maintain a general automotive transportation service, maintain the power lines, maintain the hotels, prepare food, and tend to the forests. The investment in creating Chornobyl was simply too great to write off - the power lines and support systems are still active, and engineers are developing experimental solar panels near the power plant with the hopes of changing the future of Ukrainian power to more sustainable ends.

According to the scientist, the Ukrainian government allows the administration of the exclusion zone to govern itself. This allows them to operate as a country within a country, governed by loyalists to the defunct USSR. How someone could see the utter ecological devastation caused by the soviet leadership, in a country that lost more people to the Soviet mass-starvation of Holodomor than Jewish people lost to the Holocaust, and still be loyal to the hammer and sickle, I do not know. The scientist was similarly unable to explain it. “Brainwashing, I suppose. We are so far away out here. It’s another country. Everywhere, there is monument to Holocaust. But the Holodomor? We have a single museum. Millions died, tortured to death. No one knows.”

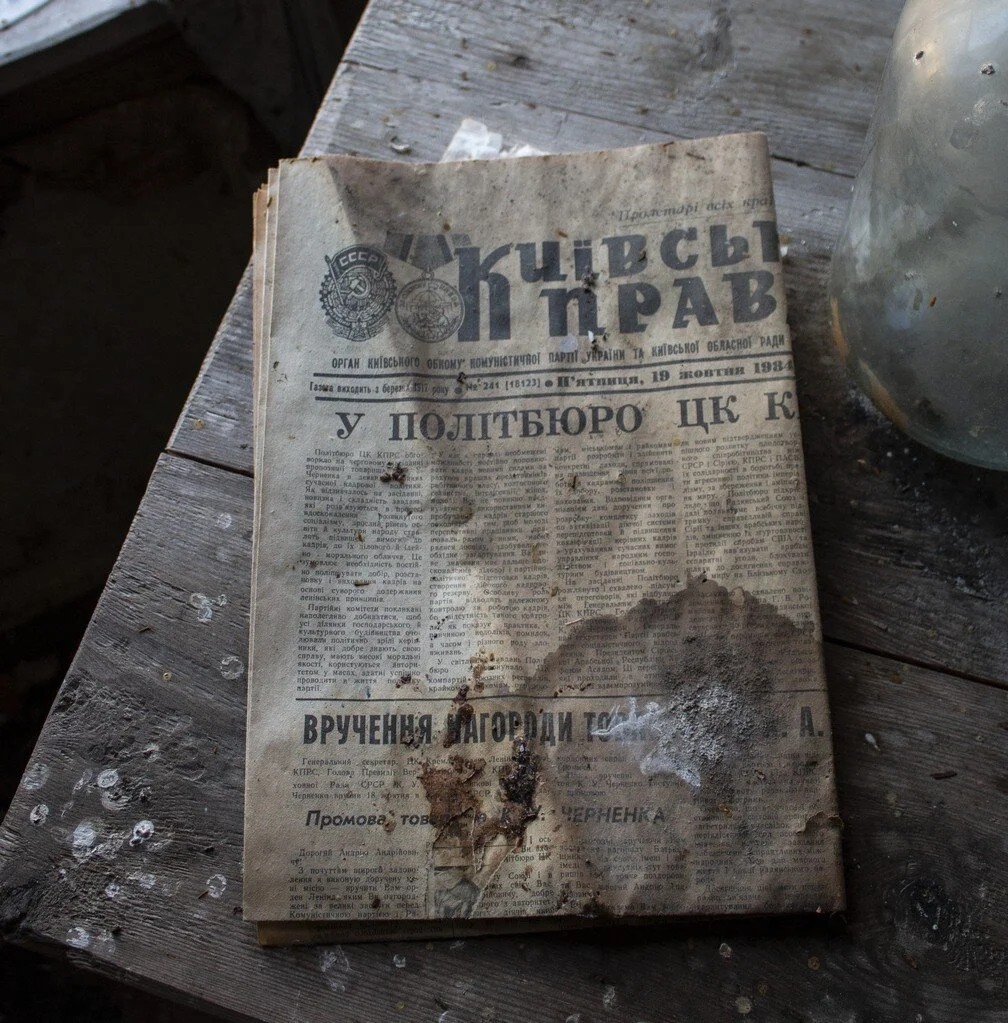

The first stop on the tour was a small, desolate village. Nature had reclaimed much of the buildings, but still a few pieces of pre-disaster culture remain, including newspapers, bottles of vodka, and rusted farm equipment. Still, out of the decay, new life flourished. Dense moss and lichen covered the ground, and trees and bushes punctured buildings.

After the first village, we entered Chornobyl. Not the power plant, but the town for which the power plant was named. This is still an occupied, officially registered town. Past the entry way, there is an installation that acts as a monument to the dozens of villages that were depopulated and evacuated - some of them permanently. Rows of signs, each one with the name of a village. If they were crossed over in red, they were evacuated. If the sign was black, the inhabitants were never allowed to return. The somber mood of the monument was undercut by the fact that it was a demonstration of the incredible corruption of the Ukrainian government - the monument consisted of a hundred meters of metal sign posts, yet cost a million dollars to install. There is a museum that is part of this same phenomenon across the road - it was created to memorialize the destruction of the villages, but it was open only done day a year, long enough for the inspector to visit and give it the OK.

Ironically enough, at the end of the row of villages stands one of the two remaining statues of Lenin in Ukraine. After the Decommunization of Ukraine, nearly all of the statues dedicated to former soviet leaders had been destroyed, and the cities, buildings, and streets were renamed to new nationalistic designations. Everywhere except Chornobyl - so Lenin, and the Leninists, remain.

Outside of the statue lay the first of the many stray dogs of Chornobyl. Perfectly docile, basking in the sun, having accepted the fact that people are not willing to pet them or offer them treats. Almost each dog we saw had an ear tag, showing that they had been neutered.

On from there, we saw an Orthodox Church, and a statue dedicated to the heroes of Chornobyl. This statue is unique for the fact that it depicts both the firefighters and the power plant workers as heroes, whereas the rest of official Soviet depictions of the disaster depicted the plant workers as being foolish and arrogant, who failed the plant and caused their own doom. In Soviet society, the fault was the user, not the equipment. One could scour Soviet databases for equipment failures and come up empty handed. Faulty equipment meant a flaw in the Soviet system, while a fault in a human being is their own responsibility.

We crossed the Pripyat river, pausing for photos and to make sure there were no guards around. In the far distance, we saw the power plant and the shining containment facility cast over it. The containment facility is both the largest movable structure in the world, as well as the largest arched structure. It is meant to last 100 of the projected 100,000 years of half life that remain in the power plant. This would be the North Star of the trip, with each new location drawing us a step closer to ground zero.

On our way towards the first main attraction of the day, we stopped by a machine shop with gas masks rotting in rusted metal troughs. This was one of the yards where enormous machines of the Soviet were maintained, and after the disaster, machines were retrofitted with cleaning equipment and dispatched to spray the streets and buildings with powerful detergents. Vast quantities of gas masks were prepared for Chornobyl and its surrounding entities, but not for the event of a nuclear disaster - they were provided in the event of a nuclear strike from the United States. There was no official plan for a nuclear accident at the power plant, because Soviet machinery could not fail, and to prepare for a failure would imply a potential fault in the faultless Soviet machinery.

We stopped at a bus stop decorated with the image of a bear made from ceramic tiles, with the signage stating that this was a bus stop for the Children's Summer Camp for the Soviet Pioneer Organization, essentially Soviet Girl and Boy Scouts. Up the road, towards the “Children’s Summer Camp”, signs warned us to stay away, as this was a top secret "Children’s Summer Camp". Further up the way, more signs warning us to go no further towards the play area. We traveled up a curving road beyond these warnings. Through the trees, we saw the top secret radar installation called Duga.

The Duga was a vast radar installation designed to listen to missile launches across the globe, specifically by listening to the changes in the ionosphere. The whole station was top secret, so everyone who worked there lived on the base, which acted as a self contained town. Workers stationed at this location would work for a period of 5 years before being transferred to a different station on the far end of the country, where, after 5 more years, they would be transferred again. On secret bases, contact with family is minimal. Wives and husbands would not know what their spouses do for a living - and often times, the workers themselves did not know exactly what they did for a living. In Soviet society, curiosity is deadly. People learned to treat ignorance as strength.

The size of the Duga cannot really be fully expressed - it is so massive I had trouble fitting it all into the camera frame, and the equipment tunnels that run along the length of the town are so long that I could hardly see the ends from inside. Essentially, the installation appears like an array of radio towers, with miles of cabling crisscrossing them like clotheslines. Before the disaster, the cabling was a loop that could be slowly rotated through the bottom of the array for maintenance. Each vertical section of tower has a number of receiver cages, each one the size of two minivans laid end to end, with those on the western end having been cut off by scrappers. Many of the cages were removed but still lay smashed and buried the dunes below. The cables have been cut in many places, and now the strands coil against themselves in the wind, and when the gusts pick up, the old array twists and sings.

In the secret town built around Duga, there were schools, dormitories, a hospital, an auditorium, a dance hall, a canteen, and a gymnasium. From the roof of the dormitory, we could see the full spread of the Duga. I never thought I’d see the Duga in real life - or anything else that I would see through the rest of this trip. Standing before the ruins of soviet secrecy left me awestruck. The huge undertaking and the ultimate failure of their efforts is something poetic - the Duga was built to listen to the changes in the ionosphere, which is something that worked on the small scale prototype. However, the ionosphere around Iceland is too chaotic for larger scale radar installations, so the Duga was never truly functional. It was built to be totally secret, but radio transmissions on this scale are fairly easily triangulated and its location was narrowed down to a small region in Ukraine.

Having left the Duga, we made our way to the fire station. This building was empty but for a model of the Duga town, including a bit of the area around it. It included some other devices that worked in sync with the Duga, but had been destroyed for scrap metal.

From there, we visited the actual children’s scouting camp that had been used as cover for the radar installation. The camp was a swath of cabins set in a beautiful, sun-dappled part of the forest. Even without the history of the area, this would be a place of halcyon beauty. I can imagine scores of children playing in the cabins, running around, singing songs, unaware they were residents of a town that did not officially exist. Now, stillness presided. Trees, flowers, and vines consumed the cabins, painting them in the gold and red of Ukrainian autumn. The crows cawed in the far distance, and the wind rushed through the trees.

As we made our way towards the center of the cabin area, my Geiger counter began to ring. I reset the threshold, sort of like a snooze button, and went further. It rang again, and we pressed the button again. We had entered the first noticeably contaminated area. We had to reset our Geiger counters over and over, eventually setting them to a different mode so that the alarms wouldn’t bother us. As our group dispersed through the woods, our Geiger counters chirped with each step and contamination bells rang in the distance.

Of the cabins that remain intact, many of them were painted with faded cartoon characters. The scientist who lead our expedition remarked that, thanks to the iron curtain, Russian cartoons were frequently just rip-offs of American classics, including Mickey Mouse and Pinocchio. He went on to add that the Russification of these anthropomorphosed animals were generally more anatomically accurate than their American counterparts. Where Mickey Mouse and Goofy were just humanoids with mouse and dog heads, the Soviet versions had the correct bowing legs and paws. I saw this again in the toys in the abandoned kindergarten in Pripyat - rabbits looked like rabbits, not humanoid rabbits.

The first day of the tour had come to an end, we went through a radiological checkpoint, and pulled in to Hotel Chornobyl. It was about as plush as you can imagine a hotel in a military cordon could be. My aunt Jan and I were able to walk around a bit and get something to eat from the canteen before being locked in the building. More dogs came to greet us, eagerly smiling and wagging their tails. Dinner was a corn soup and a pork chop with vegetables, and it was rather nice. I stayed up late, reviewing photos and writing down observations. I listened to the strays barking and the drone of distant machines. I watched the sun set through the bars on my window and prepared myself for the next days events - we would journey into Pripyat and finally approach the sarcophagus.

DAY 2

We woke up before the sun and packed up for the second and final day of the tour. Outside, more dogs had gathered. The dogs were healthy and clean - no ticks, no signs of malnourishment, and they seemed friendly and even happy. I’m sure the winters are hard, but so long as they get the food and medical care they need, I can only assume that the stray dogs of Chornobyl live an exciting life of play and exploration.

Breakfast was a salad and some kind of mashed potato with dill - every meal included dill - and a potato pancake. Once we were ready, we journeyed to the outskirts of Pripyat. At the entrance, a huge concrete sign stood with the name of the city and the date of its foundation - При́пять, 1970. Almost everything in Ukraine is made out of concrete, cement, and steel, and almost every structure is impossibly huge and imposing. This is especially true in Pripyat, where brutal authoritarian architecture symbolized unchanging power and rigidity. I stood at the sign before Pripyat and was overcome with emotion. I was at the foot of a dead city, a place that will remain uninhabitable for 100,000 years. I paused for a moment to let that reality sink in. It wasn’t the first time my eyes would well up during this excursion, and it wouldn’t be the last.

To the left of the entry lay the far perimeter of the Red Forest. When the reactor exploded, it shot a payload of radioactive dust directly up into the atmosphere, and the wind carried generally to the northwest, depositing a lethal blanket on a thickly forested area. This forest was so heavily contaminated that it was marked for destruction - meaning every stricken tree was bulldozed and buried. The forest that grew in the three decades after the destruction had been turned red by radiation - Now, the name for the forest in Ukrainian is literally “The Reddish Forest”

We pointed our Geiger counters towards the western face of the young forest and, without fail, a wash of chirps and alarms began to ring. Even the experienced scientist would not go within a few hundred meters of the toxic woods, and so it remains largely unexplored. It has, however, become a bastion of wildlife, as many of the most harmful effects of radiation take longer to appear than the average reproductive lifespan of many forest animals. It is one of many places of forbidden temptation - a place untrodden by humankind, where animals reign unhindered. I thought about how beautiful it must be, and how deadly, like a dark new Eden. A vision not meant for human eyes.

We entered Pripyat and approached the first of 16 identical apartment buildings. Shortly after the evacuation, teams of liquidators stormed each building, scouring each room with Geiger counters before defenestrating the contaminated belongings to the streets below. The more valuable goods were stolen, and the rest were buried by bulldozers in huge furrows. Now, only hollow shells of bedrooms remain, decorated with the things too heavy or cumbersome to toss out the window; a piano, an oven, a bed frame, and so on. The piano still worked, but we could not play it as it would draw attention to our illegal activities.

At the top of the building, we watched the sun rise over the dead city. In the far distance, we could see the Duga and the containment over the power plant. From the roof, the yellow, orange, green, and gold of the forest extended in every direction, all rich with the early morning light. The pale apartment buildings stood out, the only interruption from the sea of leaves.

This was the first time I could really see the full size of the containment facility, and the sheer magnitude is hard to properly express. The building itself was an enormous complex, made larger with the first sarcophagus, and then even more incredibly large with the second containment facility slid over it. The horizon was flat in every direction save for the Duga and the containment facility. It was abundantly clear that this entire region had been built to service these two objects - and now that they were defunct, the forest had come to reclaim the territory.

On the way out, I encountered one of many wild fruit trees. Berry bushes, apple trees, and other wild fruiting plants were scattered throughout the trip, flowering and laden with seeded fruit. Everywhere else, there was moss, lichens, and fungi - carpets of clumping moss sprung up in every possible place. Near a defunct basketball court, a boot print was pressed into the cement. In the heel, a vibrant green heap of moss. In the top floor of a department store, where leaky pipes had soaked the sagging floorboards, bright green moss flourished.

We passed through the first of the shopping centers - a grocery store or canteen of some kind. Grocery stores in the era of the Soviet were often almost entirely devoid of goods, and that which did occupy the shelves was in poor quality or variety. An exception could be made for the grocery stores in secret cities like Pripyat. There, the products were of higher quality and in greater supply. Now, only rust remains.

Throughout the rest of the Soviet Union, citizens had to apply to a waiting list to get an apartment or to buy a car. In some places, the wait time was 5 to 10 years. The workers of the secret bases received special treatment, and only had to wait 1 or 2 years to receive an apartment. Even then, when a person reached the top of the list, the cost of the car or apartment could have doubled, and they would be unable to pay and would find themselves at the bottom of the list once again. This bred corruption - those with access to rarer and more valuable commodities like chocolate, could bribe the administration for better placement on the list.

The next building was an athletic center with a massive diving pool with a two-level diving board, and a completely destroyed basketball court. There were documents on the ground, maps and calendars, as well as textbooks and bits of homework, all dated to 1986. As one can see elsewhere in the exclusion zone, plant life reclaimed buildings from the inside. This is a common phenomenon for abandoned buildings around the world, but the Chornobyl exclusion zone is unique in that the radiological contamination allows plants to receive the energy to grow directly from the decaying isotopes in the soil, rather than just from chlorophyll. In the exclusion zone, vines crept through smashed windows, fungal colonies, moss, and flowering plants bloomed in the decaying wood structures, and trees punched through the floorboards, and sometimes through concrete and tile, spreading their leaves and flowers in the middle of a basketball court.

At some point in the past couple decades, Stalkers ventured into the basement of the athletic center and uncovered a trove of child sized gas masks and brought them to the surface. This is the famed “gas mask room”. Personally, I don’t mind stalkers digging up historical artifacts and displaying them, or even taking souvenirs of the disaster. I fully understand the desire to have an artifact from one of the most incredible events in the 20th century. However, I find rearranging the artifacts to create a more disturbing tableau to be vulgar - the horror of the disaster is writ large in the history of the event, and it doesn’t need to be hammered home with a child’s doll with a gas mask strapped to its face, or gas masks hanging on strings from the room like ghoulish rubber ghosts. It’s not too different from the tourists of Auschwitz who have scratched the walls of the gas chambers, leaving little claw marks for morbid photo ops - as if the history of the atrocity was not horrific enough.

This is to say nothing of the obnoxious pop-culture graffiti that had been left in several places of the zone. The zone of exclusion around Chornobyl is a place locked in time, the clocks frozen, the calendars forever turned to April 1986. It doesn’t need stencils of Pikachu, or, worse still, the cartoonish graffiti making light the events that transpired. I saw spray paintings of cartoon scientists, dancing drunk with bottles of Russian vodka, standing on top of reactor control desks, or other cartoon scientists dumping green nuclear waste from a barrel. I can’t imagine the self importance of a person going to the site of one of the most significant events in recent history and defacing it with their editorialization. Imagine going to the burial chambers in the pyramids at Cairo and spray painting a cartoon about how “you know, ancient Egyptians worshiped cats back then, and now we all look at pictures of cats on our phones, so it’s like we still worship cats, you know?” There is nothing you can add to written history. Any addition is a subtraction.

Don’t sign your name on the blackboard of an abandoned Chornobyl kindergarten. Don’t write your instagram handle on the ruins of the Palace of Culture Electric. Just be a witness, not a participant, in a history that does not involve you.

The next stop was a decrepit array of concrete stadium bleachers. Many of the structures in Pripyat were had only been opened for a few days, if at all, when the disaster happened, and these seats were not likely used at all before being abandoned. Now, they are wrapped in golden trees and vines, heavy with moss, the wooden seats now deeply contaminated.

We turned the corner and saw the Pripyat Ferris wheel. The iconic image of the dead city, the Ferris wheel was originally too radioactively hot to touch, so the administration of the zone cut the cables and let the wind rotate the wheel so that the most contaminated cars are at the top. To the left, a rusted carousel still spun slowly with the wind. Further to the left, the field of bumper cars lay surrounded by grass and dead leaves, on beds of dark green moss. This amusement park would be a great luxury for the Soviet workers, but it was never opened. The disaster came before the Ferris wheel made a single revolution.

After the amusement park, we passed by and through the Palace of Culture Electric and a few ritzy hotels and restaurants. There were a few radiological hot spots along the way, and we took very high readings of alpha and beta radiation on those we could approach. Everywhere around us, the imposing Soviet architecture loomed in. Even if the promise of the Soviet Revolution proved to be true, I can’t imagine living under such austere structures.

Each stop on the tour was a step up from the last, with every new location offering greater insight to the history of the area. Our scientist was incredibly knowledgeable, and knew the ins and outs of every location we visited. The next location was just as iconic as the Ferris wheel - the abandoned Pripyat kindergarten. This place was much larger than I had imagined, and had multiple floors and a large courtyard stretched between the complex. The contents are about as grotesque as can be imagined - heaps of rotting beds, sun-whitened plastic toys, all carpeted with moldering books and crumbling plaster. With every step, the stones and shattered ceiling tiles crunched. The bed frames lay in disarray, with scattered gas masks and bed pans collecting dust in the corners. The ceilings dripped with strange white stalactites, with their requisite stalagmites spread across the ground.

We entered another school, this one laden with more contaminated treasure. I’ve spent a lot of my youth getting into abandoned buildings to explore, take photographs, and retrieve what I could. Anything recovered from a forbidden place is a cherished keepsake - even finding old photographs in an abandoned oil factory is a thrill. The wealth of historical items and objects of morbid interest forever trapped in the zone of exclusion are maddening to a scrapper like myself. I would go to great lengths to acquire single item from the zone. To stand in a destroyed library, on a heap of fully illustrated books, surrounded by framed portraits of Soviets, and to know I can’t take a single thing with me, reminded me of Dante’s Inferno, where the greedy damned attempt to drink from a river of molten gold, only to be burnt every time.

Anyone who suggests that I took any items out of the zone is spreading lies.

After scouring the school, I climbed the dirty ladder to the top of the building. I banged my head very hard on the metal bar at the top of the door frame and spent a few moments recovering. When was able to stand up, I saw the forest and the sky reflected in the pools of rainwater that collected in the sunken roof. My Geiger counter was singing of contamination. I rubbed my head and took care as a descended the ladder into the blasted hallway.

Next on the list was the police station and jail - I only have a few photographs of the jail as it was very dark and we passed through it relatively fast. The cells were built to house four inmates at a time, in horrid conditions. The scientist told us “This is a pretty nice Soviet jail. Others were much, much worse. Torture was everywhere during the Soviet era. This isn’t even a KGB jail, which is much worse.”

The next stop was brief, but extraordinary. It is one of the most radioactive objects in the zone that has not yet been buried - The Claw, the simple name for the claw used to clean up the remains of the exploded reactor 4. As we approached it, our Geiger counters began to chirp wildly before a cacophony of alarm bells rang out. Throughout this trip, the highest my Geiger counter had read was 6 microsieverts. The scientist taped his Geiger counter to a long piece of rebar and stuck it inside the claw. Towards the bottom of the pincers, where years of rain had slowly pushed the contamination downward, the Geiger counter screamed at 620 microsieverts. In terms that even I fail to comprehend, the average contamination of the zone is 20 beta decays a second. Inside the claw is around 50,000.

We left the claw and drove a short while to something I never thought I would see - The Jupiter Factory. The name was fitting for such an enormous factory. The complex used to make circuit boards, radios, and later, robots to clean out the disaster site. The sheer scale of everything in the factory was stunning - there were rows of giant vats used to acid wash computer components, vast factory floors where columns of machines once stood. In one of the later rooms, a black chunk of a graphite, used to house the reactor control rods, stood upright on the desk. Had this been used in reactor 4, it would be radioactive enough to make the entire room a dead-zone. The one in Jupiter hadn’t been put into use, so we were able to get close enough for a picture.

Outside the building, stacks of concrete stairs coiled around the side. Bright red leaves crept in, and the sun shone through them. Birds sang in the distance as the wind sighed through the trees.

We visited a scrapyard where the rusted remains of the cleanup machines lay in ruin. There were numerous machines used to clean Pripyat, but the most contaminated areas required the use of T-34 tanks fitted with bulldozer shovels. Others were fully amphibious, designed for dredging mud and swamp water that had been affected by the blast. Germany, Belgium, and Japan contributed their machines to the clean up process - there were numerous Komatsu machines in the ruins. Outside the scrap heap, mushrooms grew in abundance.

We drove closer to the containment facility and stopped at the canteen for local workers. Walking into the relatively clean, modern building, I couldn’t help but picture what it would look like abandoned. The same principles that guided Soviet architecture were present in this post-soviet structure - huge walkways, high ceilings, and industrialization in every corner. I don’t know enough about Ukrainian culinary traditions, but it would seem that they enjoy a multi-course meal more than my home country. A full lunch spread consisted of a glass of cold plums, a small salad with a slice of salami and a wedge of cheese, a bowl of tomato and meat soup, some steamed potatoes, a bit of meat, some peas, and two glasses of unknown juices. It was a lovely meal.

As we left the canteen, we saw another pair of Chornobyl dogs, eager for scraps from the cafeteria. We walked a short way, the dogs running and playing around us, escorting our group on our path. I have never wanted to pet a dog more in my entire life.

The way forward passed through some areas of questionable legality. Entering any building in Pripyat is strictly forbidden, but the laws are enforced by people who govern themselves with little interaction from the national government. We passed by a building that is watched more closely than others and saw a relatively new car parked in front, meaning a guard or a police officer was not too far away. We kept the pace and moved through the woods before arriving at the tremendous gateway of Unit 5.

It is impossible to express just how large some of these buildings are. The dense trees that surround many of the buildings conceal their size until you are at the foot of the structure. We stood at the gateway of Unit 5, an entrance constructed to allow a full freight train to pass into the main hall. Inside, you can look upwards to the crumbling ceiling ten stories above you - inner chasms so huge that complete darkness touches the walls in the middle of the vertical passageway, and sunlight fills the top of the room. The dogs waited for us at the gate as they seemed unwilling to join us as we stepped into the cold darkness of the freight hall.

We navigated the darkness quickly. I wasn’t sure exactly what the scientist was taking us to see, but given our proximity to the disaster site, I was curious. We reached the fifth or sixth floor and looked across the way to see a hole in the side of the building. From there, I am not exaggerating when I say that the spectacle was jaw-dropping. Looking out the freight window, I saw industrial devastation on a scale I had never witnessed before, with the twisted steel and concrete superstructure of Unit 5 laid bare. Beneath me, a fetid swamp of flooded cement loading docks, fed with the rusting wreckage of collapsed cranes and industrial equipment, bordered by an expanse of green and yellow trees, the view terminated by the remains of the power plant. The view was stupendous - perhaps the most inspiring of this entire journey - then we went inside again, and took a few more flights of stairs to reach the first rooftop of Unit 5, which expanded the view even more. Looking through the skeletal remains of the structure, enormous cooling stacks could be seen the far distance, and further beyond them lay the great swamp. I saw a stork land in the water below. The scientist remarked, “In Soviet Union, there was no sexual talk. No one talked about sex. Baby comes from stork.”

I didn’t want to leave, but the scientist informed us that we risked being spotted and he ushered us inside. In order to reach the other side of the plant, we had to walk across a fallen I-beam, suspended above a drop into total darkness. Jan was the first to cross. In the second room, the scientist shone his flashlight over the balcony to show us several huge circular holes in the ground.

The explosion that caused the disaster at Chornobyl occurred at Reactor 4, housed in Unit 4 of the plant. We were in Unit 5, an exact copy of the destroyed building housed in the new safe confinement structure. The scientist guided us down into the ambiguous darkness and gave us the rare opportunity to walk atop a defunct nuclear reactor of the exact RBMK model that devastated the city. If you’ve seen the HBO series, you may recall the split second scene where the reactor control rods begin bouncing up and down as the reactor reached the critical point, before exploding out the roof of Unit 4 - this room is where we walked. The tragedy is that this part of the structure is in total darkness, so I had to rely on the collective flashlights of the group and the flash of my camera to take a proper photograph. Were this Unit 4, I would be standing just above the so-called “Demon Heart” of Chornobyl, the one of the deadliest places on Earth. Given how close we came to total annihilation, this was like walking on hallowed ground.

Our tour was coming to an end - just a few more stops before we departed the zone of exclusion. The bus took us to the the foot of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Our first stop was the monument to the first 30 responders - the firefighters and factory workers who gave their lives fighting the disaster. The monument consisted of a few plots of flowers, 30 plaques with 30 names, in a disused fountain. A heartbreaking tribute to the men and women who walked into nuclear fire to save their comrades.

To the left of the names lay a great statue of Prometheus, holding the fire he stole from the Gods. While the Ferris wheel and the red and white striped smokestack have become iconic of Chornobyl, I believe the statue of Prometheus deserves to be the face of the disaster. Ironic and hubristic, Prometheus and the USSR attempted to attain the power of the gods, and in so doing they brought calamity upon their own people. This statue had once been at the front of the Pripyat theatre, it was moved after the disaster to stand by the names of those who first gave their lives.

Facing the statue is another image typical of the wild optimism of Soviet Ukraine - a copper dove, with an atom clenched in its beak. The front of the whole Soviet nuclear operation was that of “The Peaceful Atom,” a promise to use the power of fission to further mankind, rather than the pursuit of nuclear weapons. To the left, a brand new mural was being painted on the side of the power plant. The image was that of a black hand holding an incomplete atom, before a field of Ukrainian horses - The scientist was not quiet with his disapproval, saying “No one wants this painting here. They had a contest on Facebook, the winner got 200 likes, and now they are painting it here. And it is illegal, too, but the administration doesn’t care.” He looked up again at the offending mural, the scissor lift still raised to the base of the giant, unfinished atom. “No one cares.”

We pulled around to the entrance to the power plant - a place wrapped in fencing, barbed wire, and cameras. Men were at work, coming in and out. There is still an enormity of work left to be done, finishing the new safe confinement, removing and storing the waste of the old plant, and dismantling the crumbling substructure of the sarcophagus. Another small monument stood outside the gate, this one honoring all those who served the plant and helped fight the disaster. The monument, like that for the first responders and for the evacuated towns, is tiny compared to the scale of the disaster. It seemed trite.

I stood outside of the new safe confinement, which housed the sarcophagus, which housed the dead reactor of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. I had waited almost 20 years to come to this place, and had finally arrived just outside of ground zero. It was the mystery, not the danger, that drew me here, and now that I realized I can never fully enter the disaster site, I felt a little disappointed. Standing outside the building didn’t feel like it was enough for me. I want to be inside. I want to stare into the lethal core of the dead plant and see what the heart of destruction looks like. I want to see the machine that caused the downfall of the Soviet Union. To visit the outside, I was merely scratching around the itch. I realize that this is an impossible quest - no living being can go where I want to go, but I found myself looking at the enormous silver arc and feeling that same irresistible yearning that drove me there in the first place. I knew going into this that it would be the journey, and not the finale, that should draw my focus on this trip. I saw so many incredible things that lead to this point, and still more were to come. Standing outside of the plant, however, was bittersweet.

I asked the scientist how Ukrainians felt about nuclear power and he said, without hesitation, that there is no popular movement against nuclear power in Ukraine. “Nuclear power doesn’t have pollution. Yes, it has nuclear waste, but it has no pollution. You can burn coal and release pollution and radiation into the atmosphere. We still have nuclear power plants in Ukraine - no one is protesting nuclear power.”

As we left, we stopped briefly at the bridge over the coolant river. A gleaming cormorant was on the water, and it flew away as it saw us approach, leaving a series of ripples in its wake. We walked out to the middle of the bridge and looked into the deep green waters. Huge schools of carp swam slowly, their silhouettes just barely visible through the murk. The scientist looked over the edge. “There was a catfish here for a long time. Huge. I haven’t seen him in a while. Now we just have the carp. This whole place was supposed to be dammed, and they were going to make a lake at the end of the river. Now, it’s just this, but it goes on for a ways. Carp and birds.”

We drove a short ways to a dusky copse. Stray dogs walked with us, wagging hard and yipping, until we arrived at a few run-down looking barns. Outside, the horned remains of a bison skull lay paling in the sun. Inside the barns, animal cages were stacked in heaps. This is where radiation experiments would be performed on animals - minks, birds, rodents, and so on. The cages were empty - only rust, wood, and wire remain. Out the back of the barns lay the great vista - an expansive steppe that had been partially converted into a coolant pond for the power plant. Now, only the swamp remains, stretching out to the horizon where abandoned churches and villages sink into the charnel waters. Most of the places we saw on this trip revealed the startling accuracy of the STALKER video games, and this one was probably the most faithful of them all. My whole field of vision was filled with dense forests and grassy plains, with the rose and amber sky reflected in puddles and ponds. Birds flew to their perches and watched us. It was a place of unparalleled natural beauty.

Another short drive took us to our final location, one that, prior to seeing it from the balcony of Unit 5, I had not even known existed. Just outside of the power plant lay a pair of unfinished coolant stacks - the hourglass shaped concrete structures commonly associated with nuclear power. As we approached through the woods, our Geiger counters began to sing. We stopped on the road before the plant to fully behold them - again, the size was stupendous, and to see them up close was astounding. The shape of the coolant stack is designed to facilitate natural cooling of the waters heated by nuclear fission by pumping it to the top of the stack and spraying downward, where it is collected and run again until it is cool enough to release back into the reservoir. The structure we entered had an open base, and could be entered from any side - that said, this stack was unfinished so I am not sure if this would be the case were it completed.

Our Geiger counters crackled and alarms rang as we entered. Inside, I was awe-struck again at the size of the thing. The rigid, square superstructure contrasted with the smooth, curved outer structure was something mathematical beauty, a union of man man made engineering brilliance and simple perfection of natural form. It appeared to be a perfectly designed machine, where the simple task of making hot water cool, could be achieved rapidly and on massive scale. One of our group, a quiet young man from Hong Kong, wandered into the center of the stack with his camera. The scientist showed us around, warning us not to step on the highly contaminated moss that grew in verdant abundance all about the center of the structure. This is where the reality of contamination finally set in - had we not been equipped with Geiger counters, there would be nothing warning us, or the young man from Hong Kong, that the carpet of moss upon which we were standing was highly dangerous. We did our best to get him out of the moss - his English wasn’t terribly developed - but there was not much we could do once had stepped in the contamination. We would just have to see if he set off the alarms at the exit check points.

The side of one of the structures in the coolant plant had a mural of Igor Kostin, the first soviet photographer to enter the disaster site and record what he saw. He had a surgical mask on, his fingers steepled over his nose, his brow deeply furrowed by the gravity of the event he was witnessing. The Soviets had lied to the world and to their own people about the extent of the disaster - only when their hands were forced did they ever take action. I can’t image being one of the first people to see the true scale of the event - to be the first of the last Soviets to walk through the dead city, with the goal of documenting the devastation that shocked the world.

In the villages around Chornobyl, the farmers had a saying:

Next to the hill, you’re on your tractor

Across the way, there’s the reactor

If the Swedes had never told

We’d be on the tractor, getting old.

The world only knows about Chornobyl because the wind carried fallout from the plume to Sweden, and later, to London. Had this not been the case, the Soviet Union would not have even admitted the truth to their own people, and would have left them to suffer and die on contaminated soil. Case in point, the Archangelsk nuclear explosion that occurred on August 8th, 2019. This unexplained nuclear explosion killed five scientists and has caused a significant spike in gamma radiation detectable across the world. However, because it occurred wholly within Russian soil with little measurable international fallout, there is little the world can do to pressure the federation to release details about the event. Russia has stopped reporting radiation levels across the country. There could be another Chornobyl out there, erased from history.

The same can be said for prior events near Leningrad, where similar nuclear disasters, possibly even due to the same faulty RBMK reactors, have caused massive contamination of population centers, livestock, and soil. These were successfully suppressed by the Soviet Union, with only shreds of knowledge uncovered after the fall of the iron curtain. There have been, and will likely continue to be, large scale nuclear disasters for as long as we pursue nuclear power. With each one, another swath of irradiated land, lives destroyed, towns and cities depopulated.

The lies of the Soviet Union caused the disaster to occur, and exacerbated the consequences at every turn. The system put in place by Moscow caused untold horror to grip the land, and even in death, the consequences of Soviet hubris will be felt for 100,000 years. To walk among the ruins of a dead society was humbling. To capture on film was a dream. To bear witness to history was an honor.

We left the plant and passed through the first checkpoint. We had joked to ourselves about the dubious efficacy of the radiation check points, but the young man from Hong Kong set off the alarm. We waited for him to come out, watching him attempt to splash the contaminated moss off his shoes. Still, the radiation bell rang. The scientist guided him to a roadside puddle and had him jump around in the water a bit. They checked him again and he was in the clear. We applauded as he emerged. The scientist smiled for one of the few times during the excursion, “Just so you know, the next check point is five times as sensitive.” We stopped clapping.

Fortunately, we all passed through the check point with ease. I had a lot of souvenirs to buy for my friends, but I took a moment to watch the sunset over Chornobyl. I had waited over a decade to come here, and now I did. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I already wanted to go back. As odd as it may sound, I feel like I left a piece of myself in Pripyat, somewhere on this streets and rooftops of that mysterious city. My eyes welled up again, as the last of the sunlight filtered through the grass. I looked around and soaked it all in. The faded gold and brass of the trees. The sigh of the wind. A stray dog gnawing contentedly on a bone and a guard playing with a broad-shouldered puppy.

The conclusion of the trip was not something to put me at ease - there is still a large part of me that was broken by this journey. Having just a taste of a functionally limitless place of wonder, to see a handful of buildings in a city, and to spend 20 minutes at a time exploring entire industrial complexes, I felt like I hadn’t seen enough.

I’ll come back again, better prepared, emotionally, psychologically, and with a better camera.

I took a bolt from the remains of Unit 5. I didn’t set off the alarms.

![276[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58a1d85086e6c01db803d7db/1602109977431-QWXG2N3ZNDR6WU9VDN8N/276%5B1%5D.jpg)